In this Article

ToggleIn contemporary Vietnamese painting, tradition remains a fertile source of inspiration, continuously redefined by artists in their creative practices

Tradition Reimagined in Vietnamese Contemporary Art

In contemporary Vietnamese painting, tradition remains a fertile source of inspiration, continuously redefined by artists in their creative practices. Many works draw directly from traditional art forms infused with folkloric spirit, forging a distinctive intersection between past and present. From profound philosophies, legendary tales and historical narratives to the refined use of indigenous materials, Vietnam’s rich cultural heritage offers a dynamic foundation upon which artists construct their own expressive vocabularies.

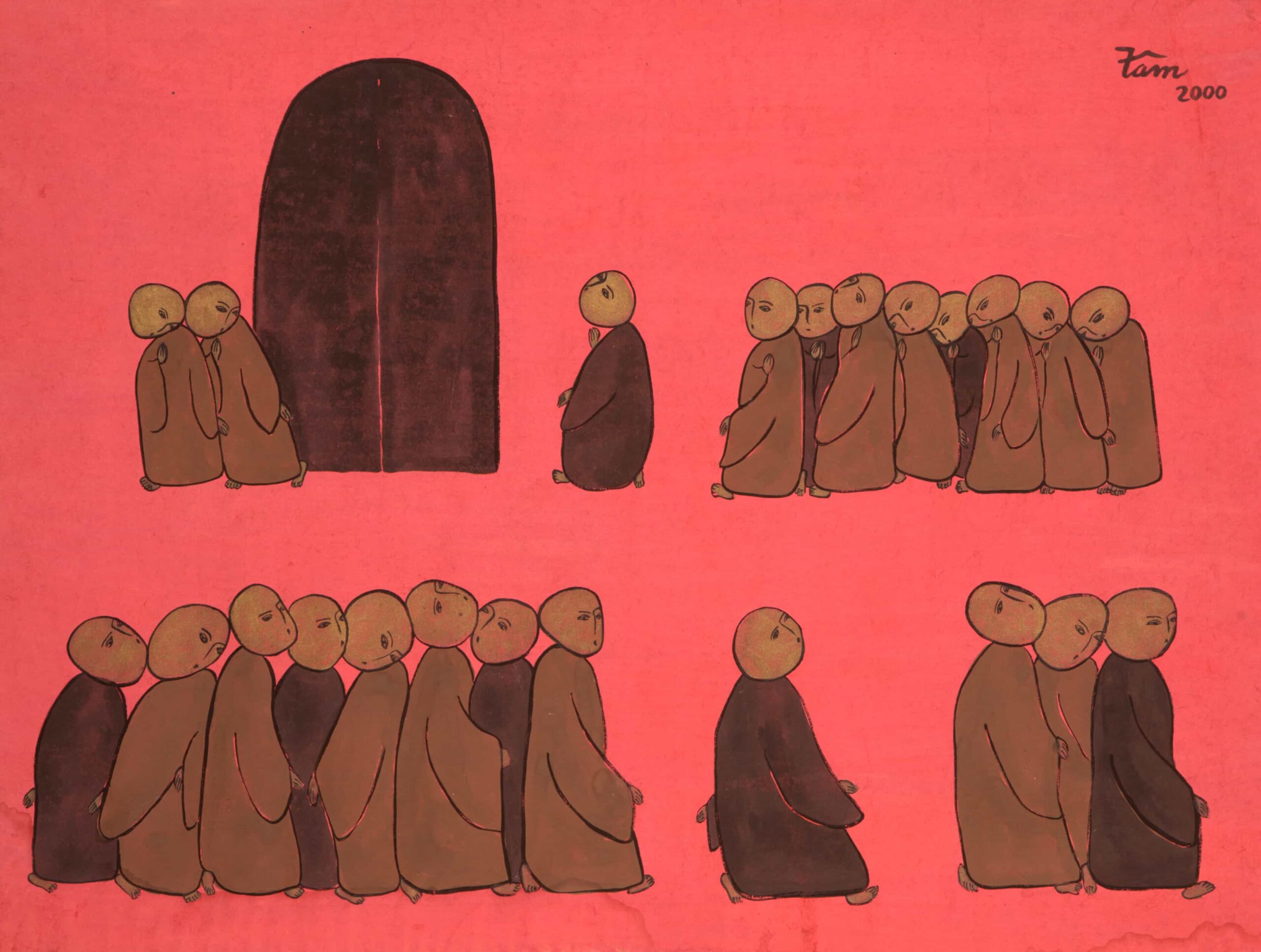

Spiritual Life and Cultural Rituals in Art

Belief systems and temple rituals have long nurtured the spiritual life of the Vietnamese people. In the work “Going to the Pagoda”, the figures of the monks are rendered with rounded, endearing lines and faces gently leaning against one another, evoking a spirit of tenderness and quiet solidarity. These monks are portrayed both as distinct individuals and as embodiments of the Buddhist principle of luc hoa — a philosophy of harmonious coexistence within diversity. Their rounded faces subtly recall the folk character So Dua from a well-known Vietnamese folk tale, a symbol of filial piety and gratitude towards those who care for us, noble qualities that also resonate within these monastic figures. Their humble, slightly hunched postures convey a quiet attentiveness, a sense of care in every step. The simplified background, rendered in a soft coral pink, heightens the purity and contemplative serenity of their monastic way of life.

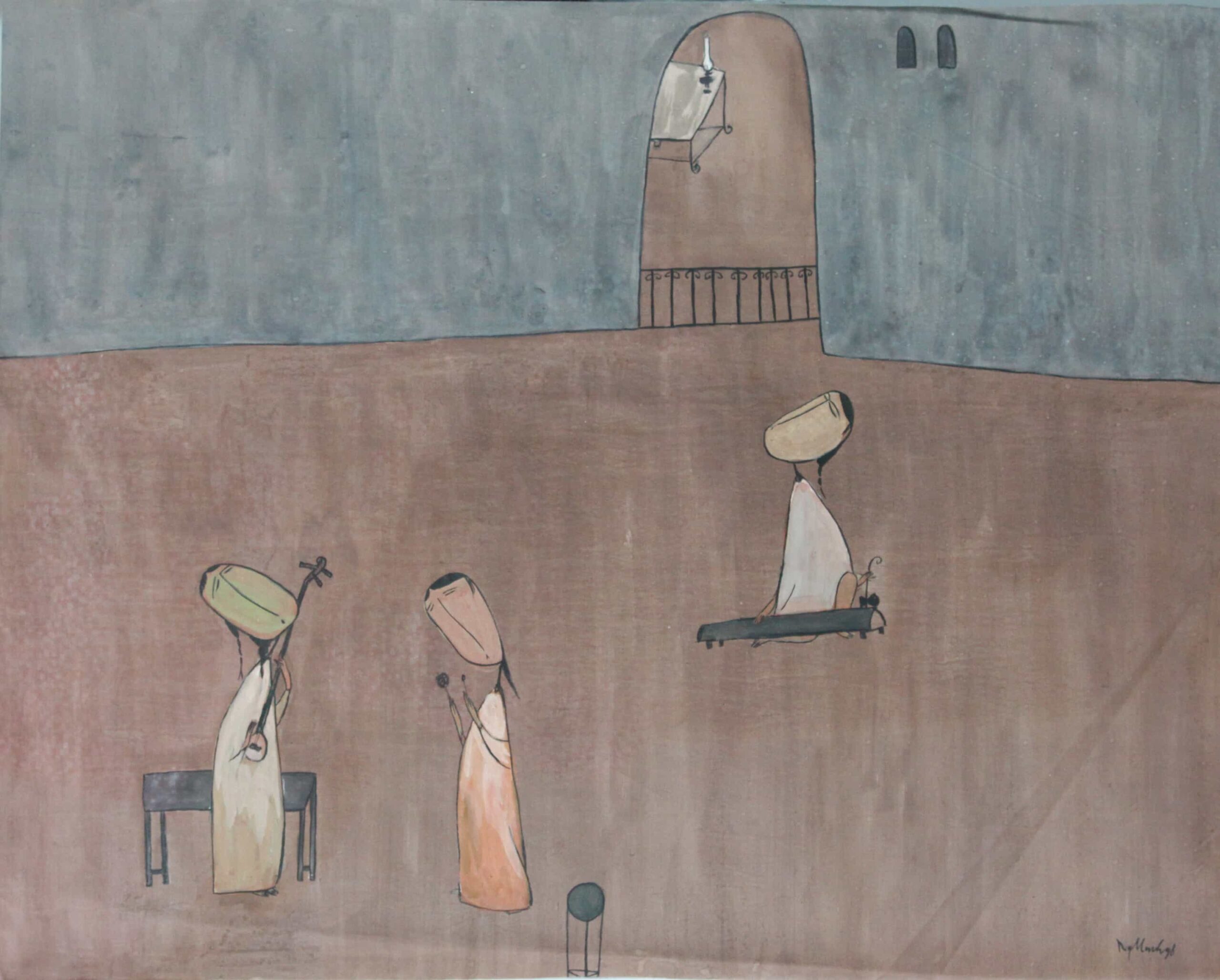

Traditional music is an inseparable part of Vietnamese cultural life, intimately tied to folk melodies, ancestral instruments, and the rustic charm of the countryside. In this context, sound becomes a vessel of collective memory, and melody becomes a narrative voice of the people. Nguyen Quang Minh depicts these scenes with warmth and intimacy, infusing them with a gentle playfulness. The female musicians are stylised with willowy figures and bean-like faces, their forms imbued with the shyness and lyrical grace of young women whose instruments echo through the stillness of night. The painting evokes a traditional musical gathering characteristic of Vietnam’s northern highlands, where three performers are depicted: one playing the gourd lute, another holding rhythm sticks, and the third playing the gourd zither.

Generational Kinship and Cultural Symbolism

In his artistic practice, Mai Dac Linh frequently draws upon cultural customs and imagery associated with Vietnam’s ethnic minority groups. In the work “Father and Son”, the two central figures are rendered in identical form, differentiated only by scale, subtly suggesting a deep kinship and ideological harmony between generations. Their appearance – clad in flowing garments, hands joined in a gesture of reverence, and heads shaved — evokes the image of meditative monks in a state of contemplative stillness. To the left of the composition, vertical elements stand perpendicular to the figures, reminiscent of sacred poles commonly found in traditional ceremonial spaces. The overall structure of the painting is carefully composed, with Mai Dac Linh orchestrating a deliberate tension and interplay between fundamental geometric forms.

Bui Huu Hung is widely regarded as a master of traditional Vietnamese lacquer painting, with much of his work dedicated to portraying historical figures. In The Mandarin, he depicts a dignified official standing solemnly, wearing a traditional turban headdress and a formal ao dai, its twin panels gently converging in stillness as he awaits the conclusion of the ceremonial burning of votive offerings. The scene is constructed through a blend of imagination, conjecture, and research, drawing upon historical context and period costume to evoke the atmosphere of Vietnam’s feudal era.

Legendary Tales and Sino-Vietnamese Heritage

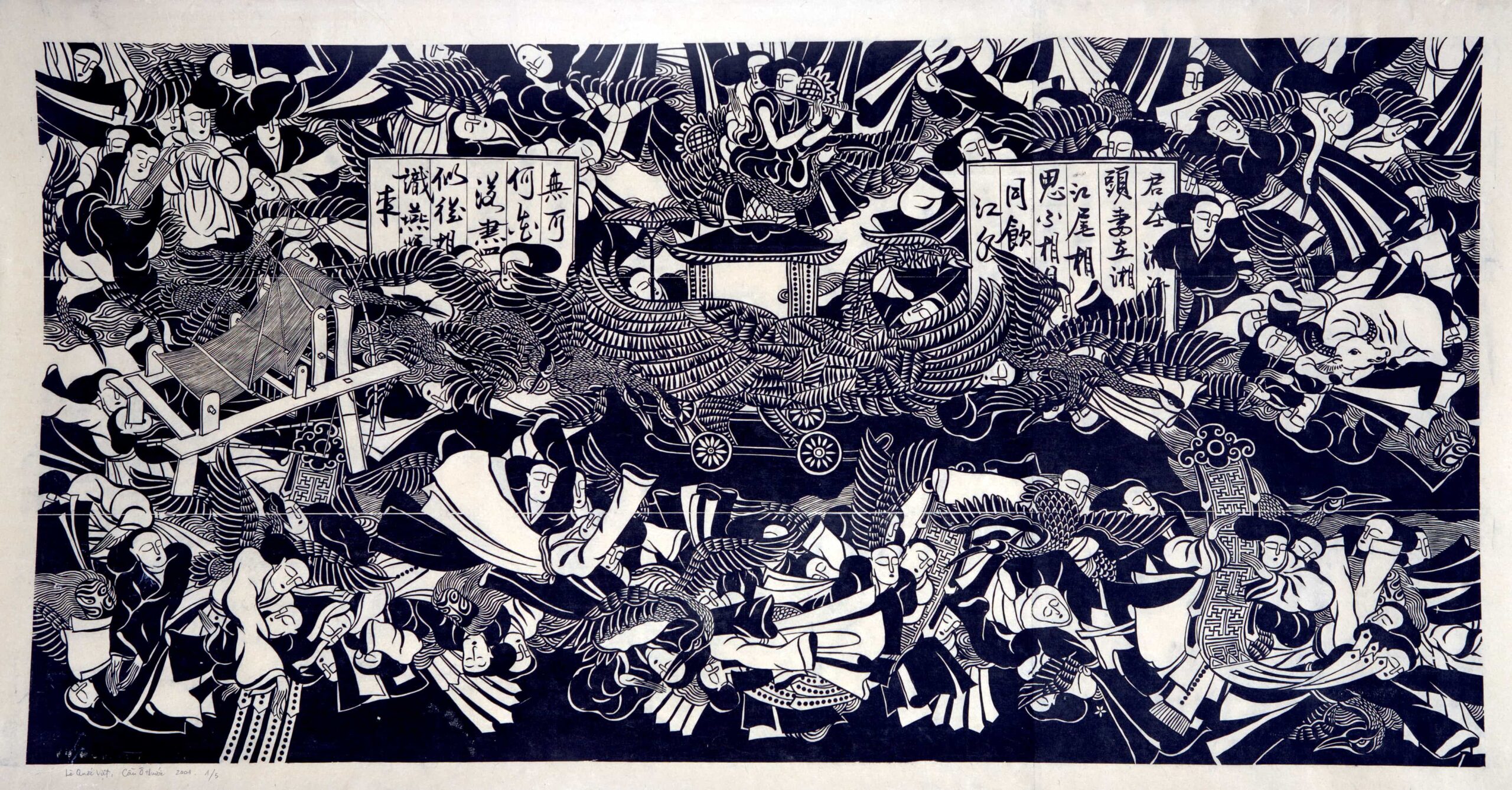

A distinctive hallmark of Le Quoc Viet’s work lies in his vibrant depictions of bustling crowds, often interwoven with excerpts of Sino-Vietnamese script that serve as textual focal points. In the piece “Raven’s Bridge”, the scene draws inspiration from the East Asian folktale of Nguu Lang and Chuc Nu. According to legend, this star-crossed couple, separated between the earthly realm and the celestial heavens, are permitted to reunite only once a year, on the seventh day of the seventh lunar month. Their long-awaited meeting takes place on a bridge formed by compassionate crows, who, moved by the strength of their love, gather together to create a passage across the sky.

Rather than emphasizing the crow bridge itself, Le Quoc Viet chooses instead to foreground the image of the entwined couple, using it as a central motif repeated throughout the composition. This repetition underscores the enduring strength of their bond while also animating the scene with a rhythmic, dynamic quality. Subtle narrative details – such as Nguu Lang playing the flute or tending buffalo, and Chuc Nu captured in graceful, feminine dance-like poses – are skilfully integrated into the work. Notably, the inclusion of Sino-Vietnamese reflects Le Quoc Viet’s deep commitment to this ancient script. As one of the few remaining scholars dedicated to its study, he uses his art to bring Sino-Vietnamese closer to the public, helping to preserve a vital yet fading element of Vietnam’s cultural heritage.

Spiritual Struggles and Buddhist Philosophy

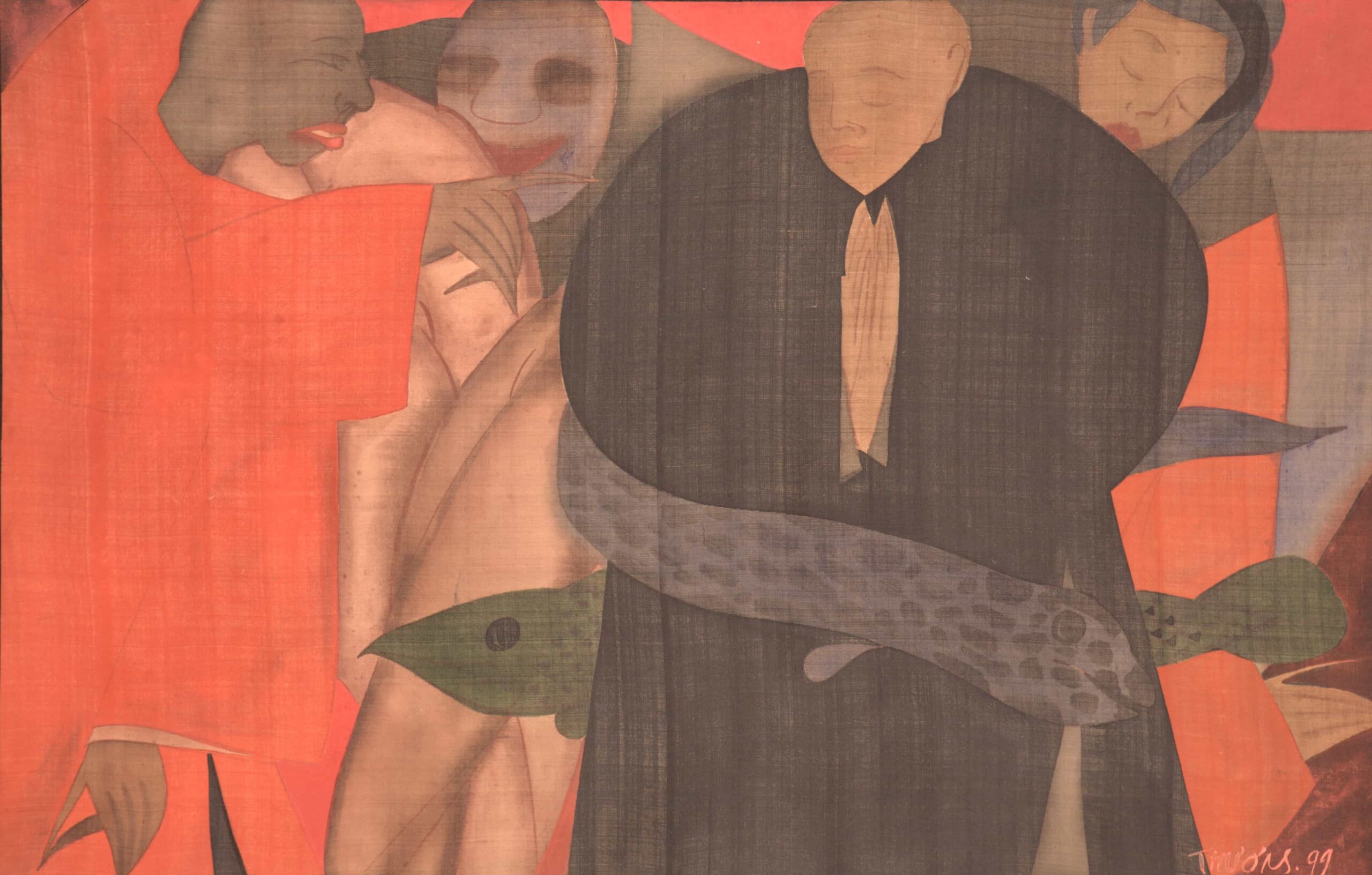

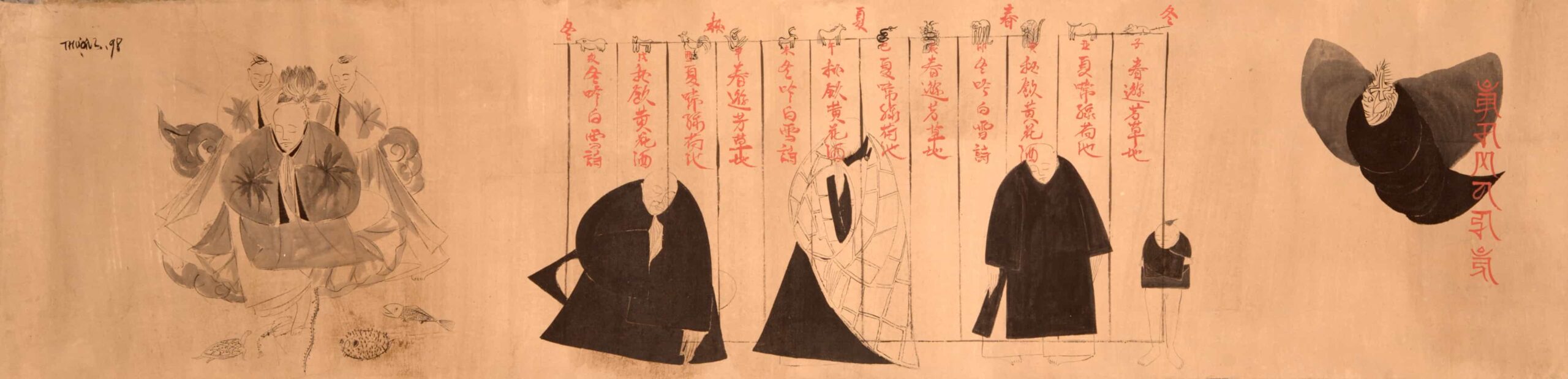

Another prominent name in discussions of tradition and faith is Phan Cam Thuong. As a scholar of language, art criticism, and artistic practice, his work embodies a deeply East Asian spirit, where Buddhist scenes, teachings, characters, and philosophies appear as part of everyday life. His approach to colour harmony and compositional arrangement consistently conveys a sense of quiet subtlety, yet never lacks intellectual depth.

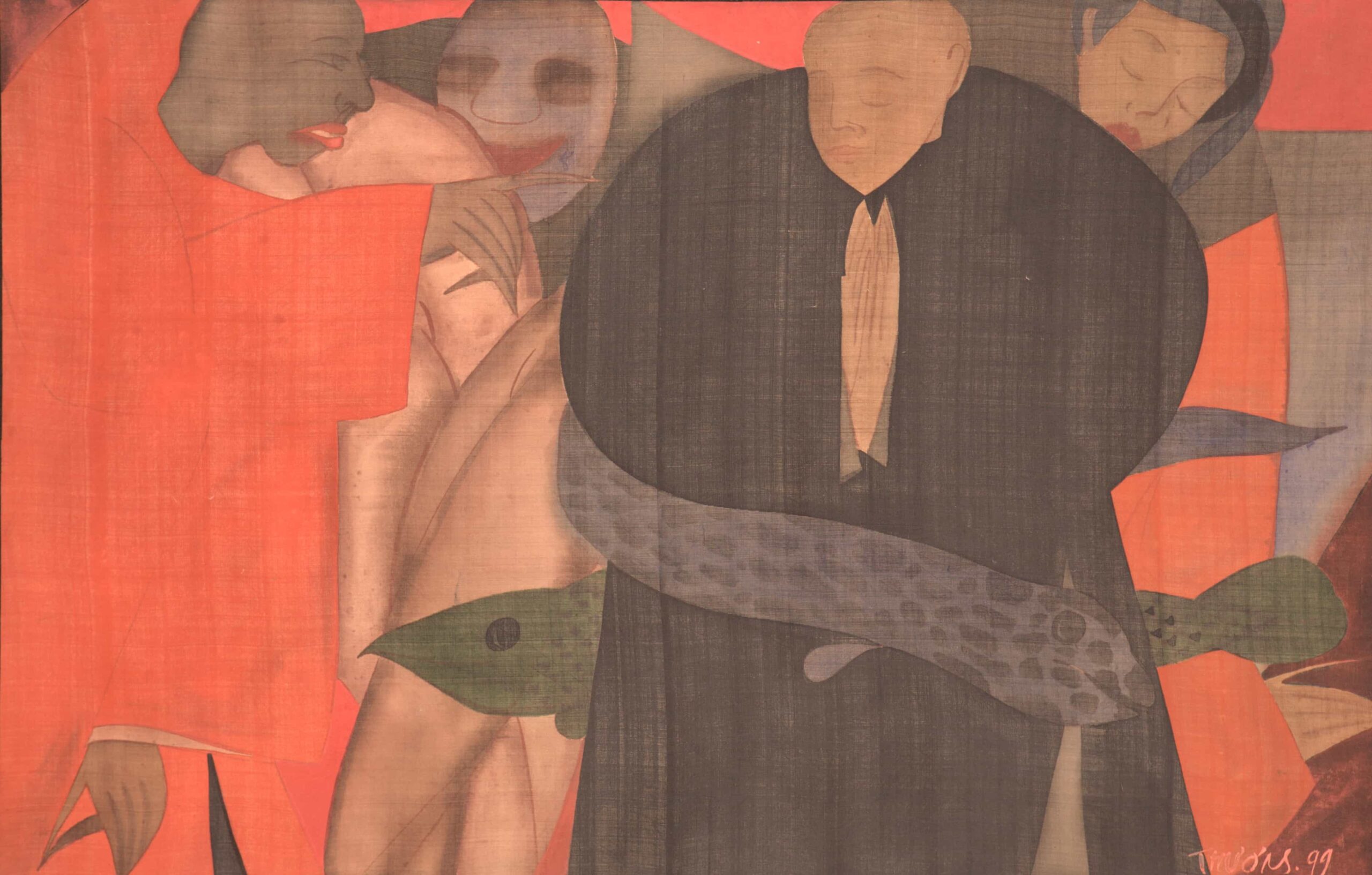

In the work “Hypocrisy”, Phan Cam Thuong presents a metaphorical depiction of the persistent temptations that a spiritual practitioner must confront on the path to inner peace. The image of a snake coiled tightly around a monk places the central figure in an inescapable confrontation with the myriad forms of temptation, ranging from seductive words and material enticements to inner turmoil and external pressures. Amidst this suffocating entanglement, the monk’s face remains serene, eyes gently closed and hands pressed together in a gesture of mindfulness, embodying stillness and equanimity in the face of life’s turbulent currents. In stark contrast, the faces of the surrounding figures – rendered in shades of grey and pitch black – bear sly, sinister expressions. These shadowy presences personify the worldly desires and corrupting forces pressing in from all sides, attempting to disrupt the monk’s state of spiritual composure.

Tiếng Việt

Tiếng Việt