In this Article

ToggleFollowing the Renovation reforms, Vietnamese artists embraced the use of found objects, transforming everyday materials into powerful symbols of freedom, identity, and social commentary

The Rise of Found Object Art in Post-Renovation Vietnam

Following the Renovation reforms, the late 1990s marked a period of deeper openness in Vietnam, allowing artists greater access to international streams of information and contemporary art theory. In this context, alongside ongoing financial constraints, the concept of “found objects” or “ready-mades”, long established in Western art history, began to be creatively embraced by Vietnamese artists. Driven by the practical need for accessible, low-cost materials such as cardboard, glass bottles, old newspapers, or scrap metal and paper, artists started to explore the expressive potential of everyday objects. This movement signalled a departure from conventional materials like oil paint, lacquer, or silk, and ushered in a new era of artistic experimentation. The reuse and transformation of discarded items became more than an economic solution; it emerged as a potent form of expression, helping to shape adaptive, improvisational practices and broadening the expressive freedoms of this era.

Rural Themes Through Everyday Materials

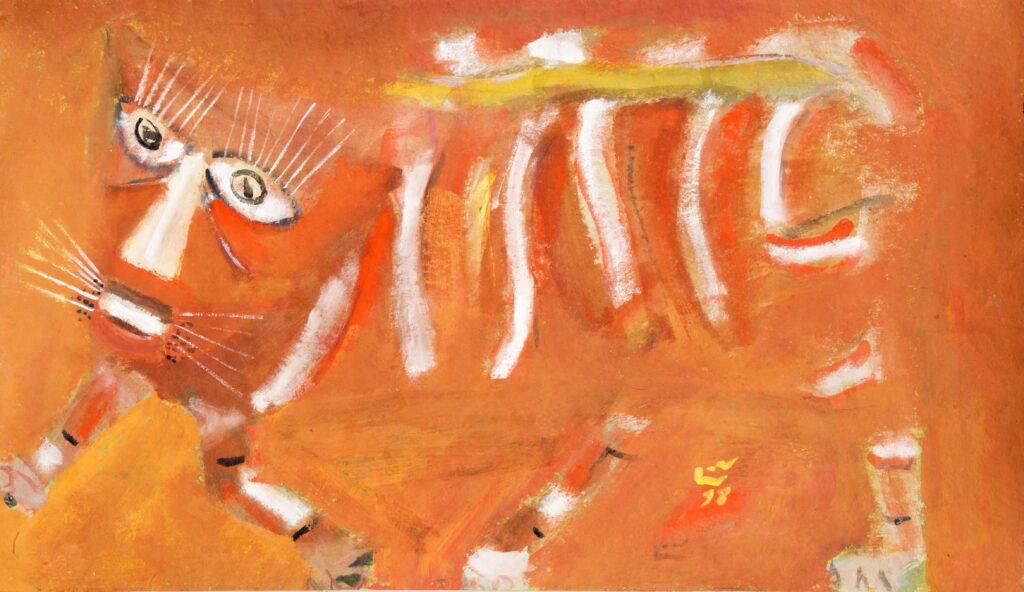

For most people, items such as used cigarette boxes, crushed containers, or chipped ceramic jars may appear as mere rubbish. But in the eyes of Ha Tri Hieu, these are precious materials – carefully cherished and given renewed life through art. Renowned for his deft compositional skills and masterful use of colour and surface, Ha Tri Hieu’s painterly approach blends the emotive force of Expressionism with the rustic simplicity of rural life. The result is a body of work imbued with both romanticism and a tender naivety, reflecting a poetic sensibility grounded in the everyday.

The work “Whisky Box 02” stands as a vivid example of this approach and aesthetic. Upon the surface of a whisky box label, Ha Tri Hieu paints familiar figures of rural life: three farmers’ heads connected by a shared kerchief, their feet rhythmically stepping onto a platform – an image evoking unity and the synchrony of labour. The motif of a farmer singing, a recurring theme in Ha Tri Hieu’s oeuvre, is reimagined here using a restrained palette of white, orange, and the original blue packaging. This minimal color scheme, paired with bold, decisive lines, conjures a scene that is at once cheerful and slightly surreal, capturing the buoyant footsteps and spontaneous song of life on the move.

Political and Social Commentary in Art

With a background as an animation artist at Vietnam Television, Vu Dan Tan nurtured a lifelong fascination with the formation of fictional characters steeped in theatricality and performative flair – an interest partly inherited from his father, the playwright Vu Dinh Long. He is widely recognised as a pioneer in experimenting with unconventional materials and was a leading figure in the experimental art movement in Hanoi.

In Cracker Elephant, Vu Dan Tan recontextualizes discarded biscuit boxes by expertly folding, molding, and compressing them, cleverly integrating the existing patterns and colors to form the distinct image of an elephant-shaped cuboid. This piece belongs to a larger body of work in which recycled boxes are transformed into whimsical characters, each imbued with a fairy-tale quality. The chosen shapes of the boxes are carefully considered, contributing to a sense of coherence and co-existence within the enchanted world that Vu Dan Tan so imaginatively constructs.

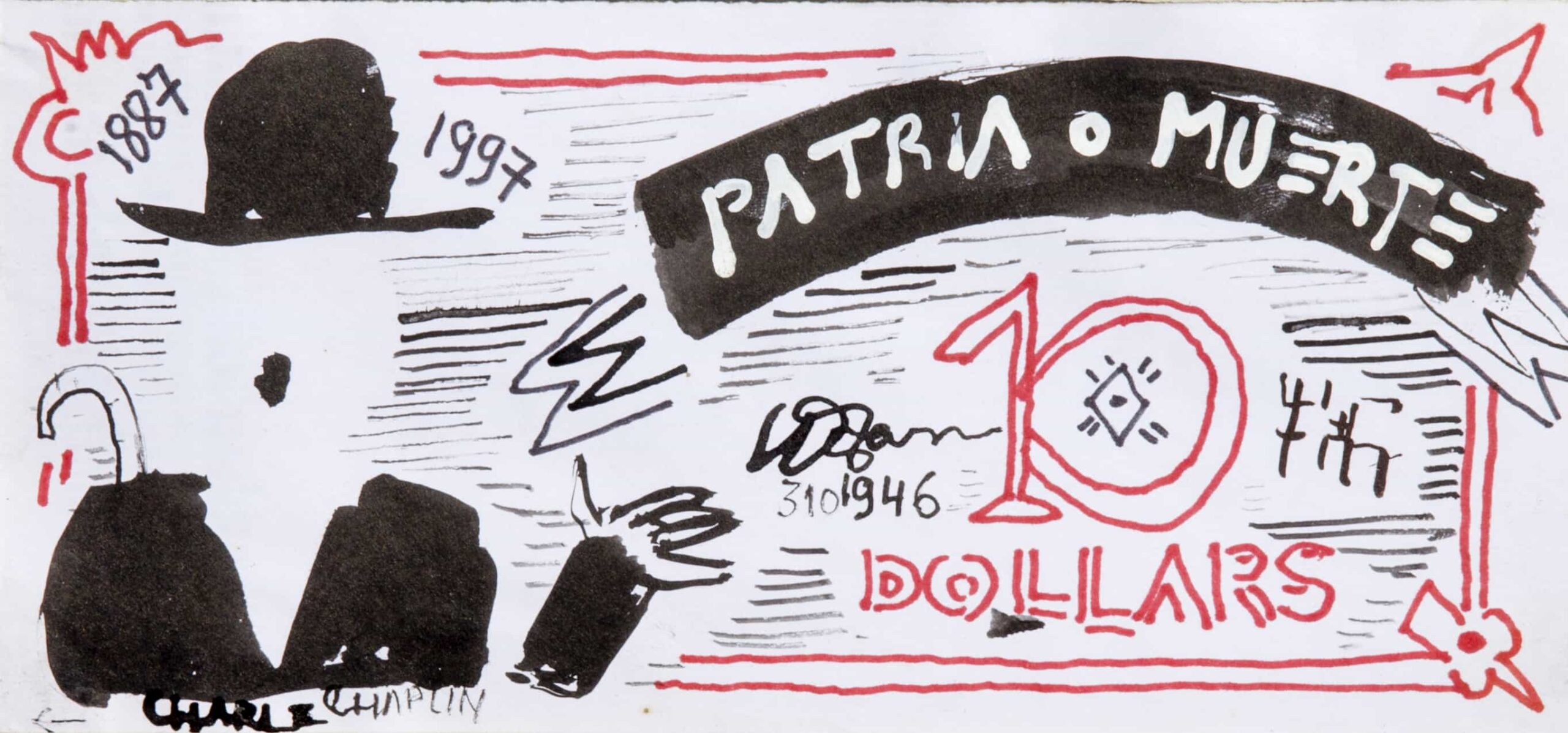

In the work “Patria o Muerte No.2”, rendered on cardboard, Vu Dan Tan deconstructs the conventional imagery of the American dollar bill to introduce layered reflections on society, economics, and culture. Part of his Money series (1990–2000), the piece moves beyond merely replicating currency iconography – it reimagines money as a discursive space for interrogating narratives of colonialism, power, and both individual and collective identity.

Patria o Muerte or “Homeland or Death” – is a renowned slogan of Cuban leader Fidel Castro, emblematic of the Cuban Revolution. The phrase encapsulates a fervent desire for liberation and a resolute prioritisation of the collective over the individual, symbolising the existential struggle for national survival.

Art as Freedom: Expanding Boundaries with Found Objects

On the surface of this banknote, Vu Dan Tan distills multiple symbolic elements drawn from historical and cultural contexts, expanding the ideological resonance of the slogan.

“1887” refers to the year the Dawes Act was passed under U.S. President Grover Cleveland. This legislation had direct and devastating consequences for Native American communities: it authorised the division and appropriation of their ancestral lands, leading to forced displacement and the redistribution of territory to white settlers. At the same time, it posed a significant threat to Indigenous cultural identity, as Native children were compelled to assimilate into mainstream educational systems, and tribal structures were deliberately dismantled in favour of individual land ownership, thus eroding long-standing communal traditions.

“1997” marks the historic moment when the United Kingdom formally handed Hong Kong back to China, ending 156 years of colonial rule. This complex geopolitical event highlighted ongoing tensions surrounding sovereignty and autonomy in the region. While Hong Kong retained its status as a major socio-economic hub in Asia under the framework of “One Country, Two Systems”, the extent and durability of its autonomy have remained points of contention and debate in the years that followed.

The sequence “3101946” marks a pivotal historical moment in Vietnam’s modern history, corresponding to March 10, 1946. This date came shortly after President Ho Chi Minh signed the Preliminary Agreement with representatives of the French government on March 6, 1946, in which France officially recognized Vietnam as a free state within the French Union. On that very day, President Ho Chi Minh sent a poignant letter to the people of Southern Vietnam, encouraging their fighting spirit and affirming that the sacrifices made by the people were bringing about real change, drawing the nation closer to full independence and freedom.

Another notable figure that appears on the face of this deconstructed currency is the iconic British comedian Charlie Chaplin. Recognizable by his bowler hat and bamboo cane, Chaplin’s “Little Tramp” character is not merely a comedic figure but also a profound symbol of unbreakable freedom. His eccentric walk and exaggerated gestures transcended cultural, gender, and social boundaries, creating a space in which the everyday person could rise above the constraints of a judgmental world. Through sharp satire, Chaplin critiqued capitalism and societal norms, turning quiet resignation into acts of subtle rebellion. Little Tramp was not just comic relief – it was a voice for freedom, waving the banner of the right to live and to be oneself, while exposing the invisible chains that capitalism so often imposes.

All of these elements were carefully curated by Vu Dan Tan and inserted into his reimagined ten-dollar bill, in an effort to awaken a consciousness of freedom – that freedom is not something to be assumed or inherited, but something that must be voiced, fought for, and openly asserted without hesitation.

These experiments with non-traditional materials, such as the “Money series” by Vu Dan Tan or the lovingly transformed packaging by Ha Tri Hieu, reflect a broader movement in Vietnamese art toward found objects and ready-mades. This practice significantly expanded the boundaries of artistic thought and the very concept of “freedom”. This exploration extends beyond national borders and political confines, inviting viewers to contemplate the perpetual struggles for freedom, self-determination, and identity unfolding globally.

Tiếng Việt

Tiếng Việt